At present, new drug compounds are becoming increasingly complex, and the proportion of poorly water-soluble drugs continues to rise. It is estimated that 40% of marketed oral drugs and 70–90% of compounds in development are poorly soluble¹. Converting crystalline active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) into amorphous solid dispersions (ASD) using polymers has become an important approach to improving the solubility of poorly soluble drugs. Since their first application in the 1970s, the number of marketed drugs utilizing ASD technology has continued to grow. Statistics show that between 2012 and 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 48 drug products containing ASDs. Although ASD can significantly enhance solubility, identifying a physically stable system suitable for pharmaceutical development remains challenging. This is due to the wide variety of polymers and surfactants used in ASD, as well as different drug loadings, which together require extensive screening. Predicting the physical stability of ASD can help eliminate unstable systems and, to some extent, streamline the screening process. This article discusses several classical and cutting-edge methods for predicting the physical stability of ASD.

2.1 Ratio of the Melting Point (Tm) of the Crystalline API to the Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) of the Amorphous API, and LogP

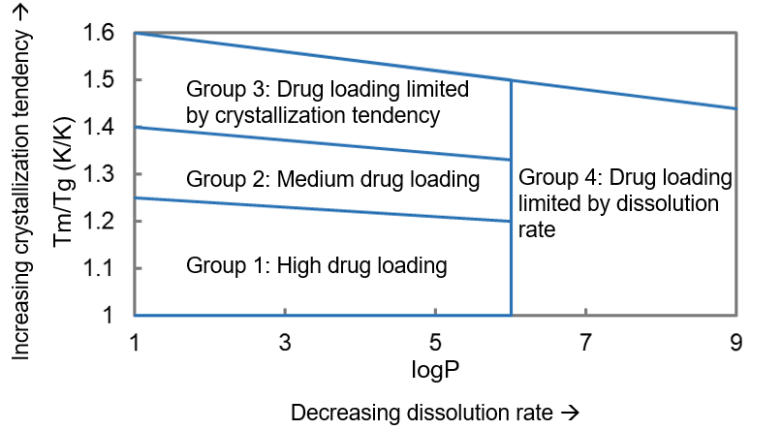

For a given compound, a higher melting point (Tm) of the crystalline form indicates a stronger crystallization driving force. A lower glass transition temperature (Tg) of the amorphous form corresponds to greater molecular mobility, which also increases the tendency to crystallize. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) can be used to determine the crystalline Tm and amorphous Tg, which can then be used to assess amorphous stability. Friesen² et al. studied hydroxypropyl methylcellulose acetate succinate (HPMCAS)-based ASD systems and concluded that, at the same drug loading and temperature, compounds with a higher Tm/Tg ratio tend to crystallize more rapidly. For compounds with an intermediate Tm/Tg ratio (1.25–1.40, Group 2 in the figure below), Friesen et al. recommended a drug loading of 35–50% to ensure good physical stability. Compounds with higher Tm/Tg values (Group 3) require reduced drug loading, while those with lower Tm/Tg values (Group 1) can tolerate higher loading. As LogP increases, the miscibility between the compound and HPMCAS or other commonly used ASD polymers generally decreases. Meanwhile, higher LogP often corresponds to increased molecular mobility in the amorphous state, requiring lower drug loading. For compounds with LogP values greater than 6, very low drug loading is often necessary (Group 4). The schematic below provides a simplified illustration of the relationship among Tm/Tg, LogP, and the drug loading ranges that enable the formation of physically stable ASDs in HPMCAS systems.

Schematic relationship among Tm/Tg, LogP and drug loading for compounds capable of forming physically stable ASDs

2.2 Glass-Forming Ability (GFA) of the API

To assess the stability of amorphous APIs, Baird³ et al. proposed a glass-forming ability (GFA) classification system. In this method, the API is first heated to melt, then cooled to a temperature below Tg, and subsequently reheated. Based on whether crystallization occurs during cooling and reheating, APIs can be categorized into three classes, as summarized in the table below. These three classes represent different degrees of crystallization tendency. Although some exceptions exist⁴, the GFA of APIs is generally correlated with the physical stability of their ASDs when formulated with the same polymer⁵. Therefore, the GFA classification of an API can be used as a predictor of ASD physical stability. APIs belonging to GFA Class III typically exhibit better physical stability when formulated as ASD.

GFA Class | Class I | Class II | Class III |

Experimental Observation | Crystallizes on cooling | Does not crystallize on cooling, but crystallizes upon reheating | No crystallization during cooling or reheating |

Crystallization tendency | High | Medium | Low |

2.3 Glass Transition Temperature of the Polymer

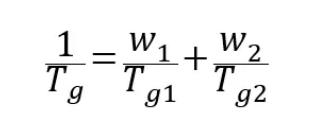

Because of molecular mobility, amorphous APIs tend to crystallize. Owing to the microscopic network-like structure of polymers, dispersing API molecules within a polymer matrix suppresses their molecular mobility. This inhibitory effect plays a critical role in the physical stability of ASDs⁶. The stabilizing effect of a polymer is often reflected in an increase in the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the system. At a fixed drug loading, a polymer with a higher Tg generally results in an ASD with a higher Tg. ASDs prepared using high-Tg polymers are typically more stable. The glass transition temperature of an ASD can be estimated using the Fox equation shown below, and this estimated Tg can be used to predict the physical stability of the ASD system.

· Tg is the glass transition temperature of the ASD (K);

· Tg₁ and Tg₂ are the glass transition temperatures of the API and the polymer, respectively (K);

· w₁ and w₂ are the mass fractions of the API and the polymer, respectively.

3.1 Intermolecular Interactions and Drug Loading

Intermolecular interactions: It is generally believed that interactions between the API and the polymer—such as hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, dipole–dipole interactions, and van der Waals forces—can stabilize ASDs. Numerous studies have examined such interactions between polymers and drugs such as felodipine⁷, acetaminophen⁸, and indomethacin⁹. Techniques commonly used to investigate these interactions include Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), among others¹⁰. Two widely applied predictive models for assessing API–polymer miscibility and potential stability are the Flory–Huggins interaction parameter and the Hildebrand/Hansen solubility parameters.

Flory–Huggins parameter:

According to Flory–Huggins theory, the interaction energy between an API and a polymer during mixing can be expressed using the interaction parameter χ. A threshold of χ = 0.5 is commonly used:

a) When χ > 0.5, phase separation between the two components is likely.

b) When χ < 0.5, the API and polymer are predicted to be miscible. A negative χ further indicates that API–polymer interactions are stronger than API–API or polymer–polymer interactions¹⁴.

Solubility parameters:

Solubility parameters describe the cohesive energy density between molecules and are defined as the square root of the cohesive energy density. The concept was introduced by Hildebrand and later expanded by Hansen. Based on the chemical structures of the API and polymer, solubility parameters (δ, in Pa¹ᐟ² or MPa¹ᐟ²) can be calculated using the Hoftyzer–Van Krevelen group contribution method¹¹. Two components with more similar solubility parameters are more likely to be miscible. Empirically¹², a difference in solubility parameters within 7–10 MPa¹ᐟ² represents partial miscibility; a value below this range indicates miscibility, while a value above it indicates immiscibility. Miscible systems exhibit superior physical stability.

Drug loading:

To improve patient compliance, higher-drug-loading ASDs allow for smaller tablets or capsules when the dose strength is the same. However, ASDs with high drug loading exhibit a stronger tendency to crystallize. Currently marketed ASDs generally have drug loadings of approximately 10–20%¹³.

3.2 Molecular Modeling and Simulation

Based on the factors discussed above—intermolecular interactions, reflected by the Flory–Huggins parameter and solubility parameters, as well as drug loading—molecular modeling approaches can be used to predict the stability of ASD systems. Predicting API–polymer interactions and miscibility is challenging due to the large molecular weight, long chain segments, and multiple functional groups of the polymeric carriers. Nevertheless, advances in computational hardware and the development of theoretical models have enabled several methods for predicting ASD physical stability, including quantum mechanics (QM) and molecular mechanics (MM) / molecular dynamics (MD) simulations¹⁴. Barmpalexis¹⁵ and colleagues used MM and docking simulations to predict the stability of two systems: ibuprofen (API)–Soluplus® (polymer)–polyethylene glycol (PEG, plasticizer) and carbamazepine (API)–Soluplus® (polymer)–PEG (plasticizer). The predicted results were consistent with experimental observations.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been applied across various fields and can also be utilized to predict the physical stability of ASDs. Machine learning algorithms, as a branch of AI, have made significant progress in predicting ASD stability. Han¹⁶ et al. compiled physical stability data for over 600 ASDs and applied multiple models, including artificial neural networks (ANNs). By training and testing on ASD stability data at 3 and 6 months, they achieved high predictive accuracy, demonstrating that machine learning can be used to predict ASD stability as well as other properties¹⁷. This highlights the promising potential of AI in forecasting the physical stability of ASDs.

[1] Kumari L, Choudhari Y, Patel P, Gupta GD, Singh D, Rosenholm JM, Bansal KK, Kurmi BD. Advancement in Solubilization Approaches: A Step towards Bioavailability Enhancement of Poorly Soluble Drugs. Life (Basel).2023 Apr 27;13(5):1099.

[2] Friesen DT, Shanker R, Crew M, Smithey DT, Curatolo WJ, Nightingale JAS. Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose Acetate Succinate-Based Spray-Dried Dispersions: An Overview. Mol. Pharmaceutics.2008, 5, 1003-1019.

[3] Baird JA, Van Eerdenbrugh B, Taylor LS. A classification system to assess the crystallization tendency of organic molecules from undercooled melts. J Pharm Sci.2010 Sep;99(9):3787-806.

[4] Kapourani A, Chatzitheodoridou M, Kontogiannopoulos KN, Barmpalexis P. Experimental, Thermodynamic, and Molecular Modeling Evaluation of Amorphous Simvastatin-Poly (vinylpyrrolidone) Solid Dispersions. Mol. Pharmaceutics2020, 17 (7), 2703-2720.

[5] Blaabjerg LI, Bulduk B, Lindenberg E, Löbmann K, Rades T, Grohganz H. Influence of Glass Forming Ability on the Physical Stability of Supersaturated Amorphous Solid Dispersions. J Pharm Sci. 2019 Aug;108(8):2561-2569.

[6] Surikutchi BT, Bolmal UB, Kumbhar SA, Shinde VR, Nadendla RR, Patil PS. Drug-excipient behavior in polymeric amorphous solid dispersions. J Excip Food Chem. 2013; 4(3):70-94.

[7] Kestur US, Taylor LS. Role of polymer chemistry in influencing crystal growth rates from amorphous felodipine. CrystEngComm. 2010, 12, 2390–2397

[8] Trasi NS, Taylor LS. Effect of polymers on nucleation and crystal growth of amorphous acetaminophen. CrystEngComm. 2012;14: 5188–97.

[9] Taylor LS, Zografi G. Spectroscopic Characterization of Interactions Between PVP and Indomethacin in Amorphous Molecular Dispersions. Pharm. Res.1997, 14, 1691–1698.

[10] Gupta P, Thilagavathi R, Chakraborti AK, Bansal AK. Role of molecular interaction in stability of celecoxib-PVP amorphous systems. Mol Pharm. 2005 Sep-Oct;2(5):384-91.

[11] Shah N, Sandhu H, Choi DS, Chokshi H, Waseem Malick A. Amorphous solid dispersions theory and practice. Springer New York;2014.

[12] Zhang J, Guo M, Luo M, Cai T. Advances in the development of amorphous solid dispersions: The role of polymeric carriers. Asian J Pharm Sci.2023 Jul;18(4):100834.

[13] Kyeremateng SO, Voges K, Dohrn S, Sobich E, Lander U, Weber S, Gessner D, Evans RC, Degenhardt M. A Hot-Melt Extrusion Risk Assessment Classification System for Amorphous Solid Dispersion Formulation Development. Pharmaceutics.2022;14:1044.

[14] Walden DM, Bundey Y, Jagarapu A, Antontsev V, Chakravarty K, Varshney J. Molecular Simulation and Statistical Learning Methods toward Predicting Drug-Polymer Amorphous Solid Dispersion Miscibility, Stability, and Formulation Design. Molecules. 2021 Jan 1;26(1):182.

[15] Barmpalexis P, Karagianni A, Katopodis K, Vardaka E, Kachrimanis K. Molecular modelling and simulation of fusion-based amorphous drug dispersions in polymer/plasticizer blends. Eur J Pharm Sci.2019 Mar 15;130:260-268.

[16] Han R, Xiong H, Ye Z, Yang Y, Huang T, Jing Q, Lu J, Pan H, Ren F, Ouyang D. Predicting physical stability of solid dispersions by machine learning techniques. J Control Release. 2019 Oct;311-312:16-25.

[17] Dong J, Gao H, Ouyang D. PharmSD: A novel AI-based computational platform for solid dispersion formulation design. Int J Pharm. 2021 Jul 15;604:120705.

Subscribe to be the first to get the updates!